Artist Profile: George Baker

Correspondent Robert Morrison provided several articles by and about George Baker, the legendary artist who appeared in so many of the early recordings of G&S. The articles are:

- "Making Three Thousand Records!" by George Baker (The Gramophone, Sept. 1934). Among other things, Baker discusses the circumstances that brought about the many recordings he made under pseudonyms.

- "Here and There," a tribute by Roger Wimbush on the occasion of Baker's 85th birthday. (The Gramophone, Feb. 1970).

- Baker's Obituary (The Gramophone, March 1976).

See also the discussion of EMI's 1970 compilation, A Tribute to George Baker.

Making Three Thousand Records!

by George Baker

["The Gramophone", September, 1934 (Vol. XII), pg. 125]

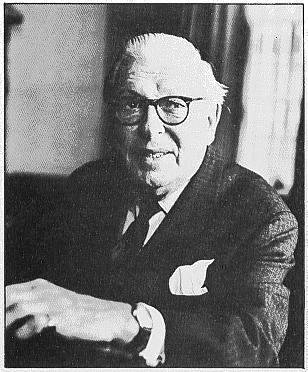

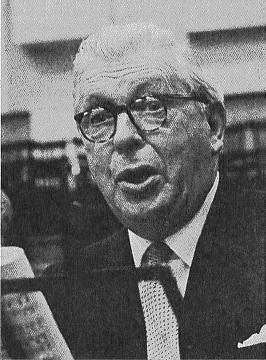

The above photograph of George Baker in later life appeared on the back of the Arabesque LP reissues of the late '20s - mid '30s D'Oyly Carte recordings. Although undated, it is reasonable to assume that it was taken around the time of the H.M.V. Sargent "Glyndebourne" recordings of the late '50s —early '60s, when Baker was in his 70s. |

For twenty years I have been making gramophone records, and there are just over 1,000 records, under the name "George Baker — Soloist." Yet, to make a rapid calculation, there must be well over 3,000 records containing that voice. In my early days singers had to work like old-time town criers to succeed on the gramophone. Those 3,000 records, stretching one behind another back over twenty-five years, seem to epitomise my singing history. Many of them are of duets, trios, quartets, and so on. The earliest ones, however, although actually sung by George Baker, are under different noms de plume, or should it not be noms de chanson?

Nowadays few singers of repute would consent to any name but their own being placed on a record label, but in 1906 this was as harmless a trick as is the appearance to-day of a "lunch edition" of an evening newspaper at 10 o'clock in the morning! The reason for this amiable fiction was that with the old recording instruments a voice either recorded well or not at all. Unless a voice was 100 per cent. gramophonic it was of no use to the gramophone companies. They had such difficulty in finding suitable voices that, in order to give a semblance of variety to their catalogues, they gave each singer two or three names and hoped the public would not recognise the remarkable resemblance between the voices of two different singers.

I began recording just for fun. Haydn Draper, the now famous clarinet player, and I were fellow students at the Royal College of Music. We were interested in gramophones, for the change over from cylinders to discs had just taken place. One afternoon he suggested that we might have a bit of fun by going to a gramophone company and asking for a test. I agreed and we made our way to the old Pathé Frères studio in Lamb's Conduit Street, off Theobald's Road. I was twenty-one at the time and had just come from Birkenhead, with a four years' scholarship. I was still wearing a cap and must have looked like a big schoolboy.

However, I was given an audition and sang "Tommy Lad." The accompanist put me down as an "extra special" singer of "Tommy Lad." I heard no more till twelve months later, when I received a letter asking me to call at the studio. I went along in the afternoon, but they could not believe I was the boy singer of "Tommy Lad"! That was because I wore a top hat and frock coat. They were not convinced until I sang "Tommy Lad" again and they had compared it with the record. I made two more records, "Nellie Deane" and "I'm coming through the corn, Sweet Eileen," for which I was paid four guineas. Shortly afterwards I was put under contract by Pathé Frères, later by the German Beka Company and His Master's Voice Company, for whom I have recorded ever since.

Peter Dawson, Mark Hambourg and I are the only three original record-makers left who are still recording regularly. We worked really hard in those days, for one song had to be sung perfectly at least six times. The records thus made would be played back again and further records made from them. The conditions under which we recorded were crude in the extreme. We sang in a tiny bare room and into a big tin trumpet which was connected direct to the recording needle by a rubber tube. We sang collarless and in shirt sleeves, for the place quickly grew stifling. When electrical recording came in, this was all changed and we now sing into microphones in beautiful rooms, not unlike broadcasting studios.

The records that have made more friends for me than any others have been those of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas. Although I am identified by thousands of Savoy Opera lovers with the George Grossmith parts — Ko-Ko, Jack Point, Bunthorne, the Duke of Plaza Toro, and the rest — I have never played any of them on the stage. Recording makes cowards of many of us, and although the regular members of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company must know their parts inside out, Darrell Fancourt and poor Bertha Lewis were the only two who dared record without their vocal scores.

The first time we recorded the operas was in the days of the old tin trumpet, and principals joined in, all the chorus-singing. When it came to our turn to sing in concerted numbers we elbowed our way through the other singers to get to the trumpet in time. Nowadays, there is a profusion of microphones and the principals do not sing in the choruses. A "mixer" blends the sounds from the different microphones into an harmonious whole, much the same as in broadcasting.

I have met most of the outstanding figures in the world of music at the gramophone studios, and find them a fascinating study. There is that great-hearted giant Chaliapine [sic], with whom I have often sung in recording Russian operas. He is very sensitive and is easily cast down in spirit if he thinks he is not singing his best. I remember on one of his "off days" he tore his music in shreds and stamped on it, and we had to soothe him like a child before he would go on singing again!

Melba had very decided views on when she was singing at her best. If a record did not please her she would sing it again, but she was not exactly the soul of patience and if she decided that a record was suitable nothing on earth would induce her to repeat the song, even if suggestions for improvements were obviously good ones. The personalities of conductors are also extremely interesting. Albert Coates is so energetic that he is physically exhausted at the end of a session. When he arrives at the studio he is accompanied by a valet carrying an open- necked cricket shirt and a pair of flannel trousers. If he has two sessions he has to change into a dry shirt before he commences a second session!

As a direct contrast there is dapper Dr. Malcolm Sargent, who displays the most extraordinary energy of any man I have ever known and yet is as unruffled and cool at the end of six hours' recording as when he started. There is not even a hair on his head out of place. I have always thought Sir Edward Elgar the most typical example of what is known as "a fine old English gentleman." Sir Henry Wood works by the clock, both at rehearsals and at performances, and I consider him the most systematic worker in the world. Certainly he is the most knowledgeable person we have in English music to-day.

Here and There

With Roger Wimbush

[The Gramophone, February 1970, (Vol. XLVII); pg. 1264]

George Baker |

In the summer of 1939 London enjoyed a music festival, probably unparalleled in its history, and the like of which has never been attempted since. With Toscanini at Queen's Hall and Beecham at Covent Garden, even the 'fringe' events took on an aura of splendour. Looking back it is interesting to recall Betty Humby and William Glock playing together, as did Aubrey and Dennis Brain. Rudolph Bing was among a starry committee, and always when work is to be done George Baker, ARCM, was Honorary Treasurer. When all was set up, and the programme book was in every drawing room, it was discovered that the name of Sullivan was missing, and this led to the staging of an extraordinary concert given at Lancaster House, now the Government Hospitality centre, but then the home of the London Museum. The Boyd Neel Orchestra, suitably augmented, was engaged, as was Irene Eisinger, who was in that year's Glyndebourne Mozart cast, and George Baker, the whole directed by Sargent. In the course of these proceedings Mr. Baker performed a feat that would have made Manuel Garcia himself wince by singing the composer's three great patter songs in a row. For many of us in that audience sitting on the great staircase it was a memorable occasion, both vocally and also, be it said, in hearing for the first time the ingenuity of the accompaniments.

This month HMV are issuing "A Tribute to George Baker" on the occasion of his 85th birthday [a review by W. A. Chislett appears on page 1326 —Ed.]. On it readers who somehow missed the originals can hear these unique performances. There uniqueness resides in the fact that in spite of the speed and the immaculate diction, the songs are beautifully pointed and they are sung without a trace of parlando. That is why these are among the historic performances of the gramophone. What is extraordinary is that although in his youth George Baker appeared on the stage he has never professionally appeared in any Sullivan opera! The record will also include his 1916 recording of Myself When Young (accompanied by Madame Adami) and made "under the direction of" Liza Lehmann, three of Quilter's Shakespeare songs and songs from Fraser-Simson's settings of Lewis Carroll and A. A. Milne, all with Gerald Moore. Here Mr. Baker links the songs with narrative and shows himself as fine an actor as singer. We have had so many coy Alices that HMV might consider a straight reading by Mr. Baker, who like Humpty Dumpty can give to words a wealth of meaning by his complete mastery of articulation.

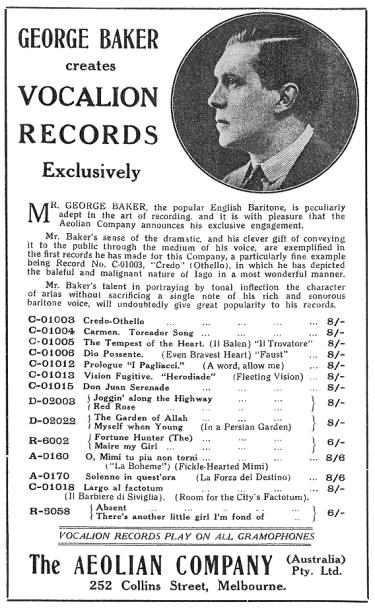

George Baker toured Australia for J. C. Williamson Ltd. in 1922–23, appearing as Lord Harry Coe in the musical revue The Peep Show, (which had originated at the London Hippodrome), and revivals of The Lilac Domino (as the Hon. Andre d'Aubigny) and Sally (as Blair Farquar.) Whilst in Australia, Baker made a number of recordings for the local Aeolian Company, and this following advertisement appeared in the theatre programme for the Melbourne season of The Peep Show, which opened at the Theatre Royal on Saturday, 21st October, 1922. |

Dining the other evening at the Bakers's beautiful London home, the candles playing on the portrait by James Gunn and the table presided over by Mrs. Baker (the charming Olive Groves); I was reminded that George Baker was our first English Klingsor on record, as he was in the earliest English Salome and Beethoven Ninth. He made two complete cycles of Gilbert and Sullivan between 1918 and 1962, including the last Sargent recordings on HMV when he was in his seventies, the Iolanthe, in which he sang the Lord Chancellor with a starry cast including Heather Harper and April Cantelo in comprimario roles, probably musically the composer's finest achievement.

No man has served the industry with greater devotion, nor over a longer period. He made his first records in 1909 for Path´ Frères, and his work covers a remarkable field, including dance-band vocals, hymns, popular duets, the poetry of Walter de la Mare and the famous "Departure of a Troopship", virtually playing all parts! His early pseudonyms included Arthur George, Walter Jefferies, George Portland, Victor Conway, Victor Norbury, Leslie Milton, George Barnes and Walter Duncan. His last recording was Ruddigore in 1962 when he sang Robin Oakapple at the age of 77, but he appeared 'live' at the Royal Festival Hall in a costume performance of Trial by Jury when he was 81.

Apart from this amazing recording history spanning 53 years, the world of British music is greatly in his debt. He was the BBC's Overseas Music Director for three years, and his untiring work for the Royal Philharmonic Society, much of it of great delicacy and calling for administrative skill of the highest calibre, will not be forgotten; nor will his work for the Savage Club, of which he was Honorary Secretary and a trustee for many years. Today, looking remarkably fit and agile, he is as likely to be seen in the Long Room at Lord's as in the studios, and his criticism of some batsmen is as constructive and as kindly as it is of some singers. Surely every reader will wish this doyen of English singers and lifelong worker for the art many happy returns of the day as we listen again to "the very model of a modern Major-Gineral".

Obituaries

George Baker (February 10th, 1885 - January 8th, 1976)

[THE GRAMOPHONE, March 1976, (Vol. 53); pg. 1453]

With the death of George Baker, a month short of his 91st birthday we have lost what surely must be the last direct link with the really early days of recording. He made his first recording in 1909 for Pathé Frères and his last, as Robin Oakapple in Ruddigore, in 1962 at the age of 77. But even this was not the end of public career for four years later he appeared in a costume performance of Trial by Jury in the Royal Albert Hall.

Born in Birkenhead, George Baker took up the violin, flute and piano as a child. He then studied singing under John Acton and eventually won an open scholarship to the Royal College of Music where he worked under Gustav Garcia, taking his ARCM for singing in 1911 and being awarded a Patron Funds Grant for further study in Milan in 1914. As early as 1901, when he was only 16, he became organist and choirmaster at the Woodford Parish Church in Cheshire, and between 1903 and 1906 he served in a similar capacity at two churches in Birkenhead.

In later years he rarely appeared on the operatic stage but in the 1920s he sang with both the Carl Rosa and British National Opera companies. He was never a member of the D'Oyly Carte Company but no-one knew the Savoy operas better. He sang Ko-Ko in the first complete recording of The Mikado (1918), of which the cast included also Ernest Pike, Edward Halland, John Harrison, Robert Radford, Violet Essex, Bessie and Sarah Jones and Edna Thorton, and went on year by year to complete the cycle, re-recording them in later years, in a series which culminated in the 1962 recording of Ruddigore referred to above. He was also one of the principals in the first English recordings of Wagner's Parsifal, Coleridge-Taylor's Hiawatha, Strauss's Salome and Beethoven's Choral Symphony. His versatility was, however, enormous. In addition to the music by which he became best known he was not above singing the vocals in dance band records and, as Roger Wimbush reminded us when commemorating Baker's 85th birthday in February, 1970, he "virtually played all the parts in a one-time famous record called The Departure of a Troopship".

Many of these records were issued under a variety of pseudonyms. It may be doubted if Baker himself knew under how many names he had recorded but they certainly include Arthur George, Walter Jefferies, George Portland, Victor Conway, Victor Norbury, Leslie Milton, George Barnes and Walter Duncan. And, of course, he was the splendid 'Uncle George' in an immensely popular early series of children's records.

Of his many attributes perhaps the greatest, over and above his innate artistry, was the perfection of his diction. Every word came through and at its true value, even in the most taxing of the Gilbert and Sullivan patter songs. He was a great vocal actor as well as singer. And not only was he a great singer, he was a splendid, indefatigable and much sought-after administrator. No-one has ever served music in Britain longer or more faithfully in this capacity. He was the BBC's Overseas Music Director from 1944 to 1947, for thirty years he served the Royal Philharmonic Society as committee member, treasurer and chairman, and he was for long the Honorary Secretary and a Trustee of the Savage Club. In addition he served as Secretary of the Orchestral Employers' Association and as a member of the committee of the Musicians' Benevolent Fund. He was also, incidentally, a very familiar figure in the Long Room at Lord's, overlooking which ground he lived for a long time before retiring to Herefordshire a few years ago. His first wife, Kathleen Hilliard, was a charming singer and delightful person who died tragically young in 1933. His second wife, Olive Groves, was another singer of charm and distinction and who went on teaching until near her death in 1974.

One hopes that such a man will be commemorated in a practical way, perhaps first of all by EMI with the reissue of HQM1200 (2/70) which contains some of his recordings between 1916 and 1933.