Civic Light Opera Company of New York City Mikado (1932)

Reported by Bruce Miller

Civic Light Opera Company of New YorkCity |

|

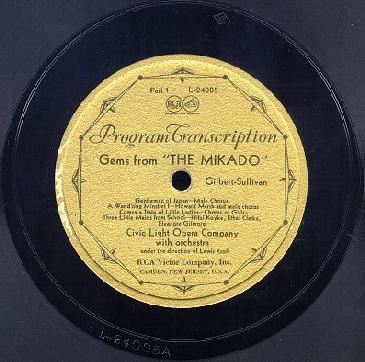

In 1932, RCA Victor issued two-record sets of "Gems from The Mikado" and Gems from Pirates of Penzance by the Civic Light Opera Company of New York City. They came out on a short-lived "Long-Playing Records" format that RCA initiated in 1931.

These were sold as two separate 10" doubled-sided "Long-Playing Records" (no album included) with catalogue numbers L-24005 and L-24006. By the 1934 catalogue there was a slide automatic version available, again as two separate discs without an album: record numbers AL-24023 and AL-24024.

The Victor Company had long been famous for issuing "Gems from" records of operas, operettas and musical comedies. These were generally in the form of a single 12" 78 side lasting about 4 to 4 1/2 minutes. They consisted of continuous medleys using, usually, only snippets of the most famous melodies from these works. There would be a house group such as the "Victor Light Opera Company" which would alternate choruses with various soli, with orchestral accompaniment. Occasionally, the company would devote two sides to a particularly well-known piece, and in fact did so with Pinafore (recorded 1912) and Mikado (recorded 1916).

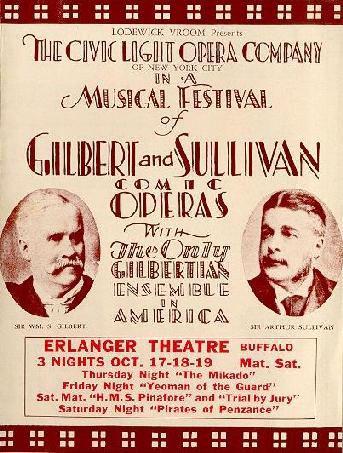

Civic Light Opera Company Brochure |

This particular "Gems" release is different. It contains approximately 28-30 minutes of music, or roughly six to seven times the length usually allotted a "Gems" issue.

In the 1930's, Victor featured this set in advertisments which also included all the D'Oyly Carte complete operas in their catalogue, directly under their Long-Playing version of the complete D'Oyly Carte Pinafore. So, the company evidently felt this set of "Gems" was significant enough that it be included with the complete sets rather than with their other "Gems" issues.

For the recording, Victor obtained the services of a well known troupe that had given professional-level performances in New York and on tour. This example of the American performing tradition between the two World Wars is both illuminating and disappointing.

The contents, as given in Victor's catalogues, were as follows:

- L-24005:

- Gentlemen of Japan – A Wand'ring Minstrel I – Comes a Train of Little Ladies – Three Little Maids from School – Finale, Act I – With Aspect Grand [sic] – He's Going to Marry Yum Yum

- L-24006:

- Braid the Raven Hair – The Moon and I – The Daughter-in-law Elect – My Object All Sublime – The Flowers That Bloom in the Spring – Hearts Do Not Break – Willow, Tit-Willow – For He's Gone and Married Yum Yum – With Joyous Shout

As snapshots of an actual professional company of the early 1930's, these records succeed in conveying vividly one company's idea of how to present G&S, unrestrained by the usually long arm of the D'Oyly Carte. The inevitable conclusion is that the D'OC, judging by their recorded output of the same vintage, deserved its reputation for setting standards. They outclass the Americans in nearly every aspect.

One might expect that an American company would have a style somewhat different from an English one, but in fact the CLOC seems heavily influenced by the D'Oyly Carte manner of the day. They just don't execute as well, and in an attempt to be "authentic," they exaggerate — almost in a caricature of the D'Oyly Carte style.

D'Oyly Carte featured singers who could act, usually not bona fide opera singers (not during this era, anyway) and often not even classically trained singers. The CLOC did likewise, except that their "singers who could act" usually didn't do either as well.

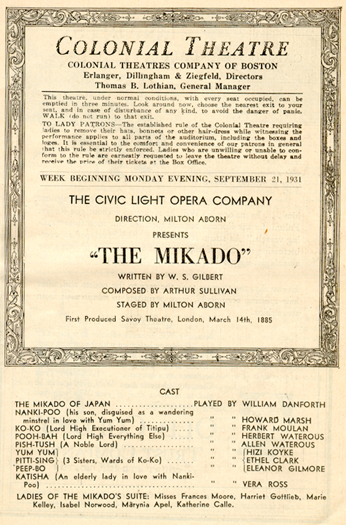

A program from the Colonial Theatre (Boston), where the Civic Light Opera performed The Mikado the week beginning Monday, September 21, 1931. Note the proximity in time to the early Victor lp, and how many cast members are those featured on the recording. |

Frank Moulan, who is credited with three roles on this recording (probably as a Depression-era economy measure) has, at best, a satisfactory voice. In his straight singing of The Mikado of Japan, he just has the lower range with not much to spare, and sings with little character. His Ko-Ko, evidently copied from the D'Oyly Carte recording, seems calculated to emulate Henry Lytton's threadbare singing voice, fully disintegrating on the high notes.

Moulan is identified as singing the role of Pooh-Bah as well, but the only solo line for this character included in this recording is in the first act finale, just before a line of Ko-Ko's ("To ask you what you mean to do / We punctually appear"). If Moulan indeed sings this line, he makes a fast and extremely adroit change into his "Ko-Ko voice": just possible, but not likely. If it's another singer, he is unidentified and not particularly exceptional. Moulan is also credited with Pooh-Bah's ensemble participation in "The flowers that bloom in the spring" and in the Act II finale. If it's Moulan in either instance, he's singing some wrong notes.

Howard Marsh is vocally uneven as Nanki-Poo. Perhaps he was nervous; sometimes he sings rather attractively, but at others his voice seems tight and unresponsive. He is also responsible for a glaring error in "A wand'ring minstrel": he tries to end the first "sorrow" passage on a full, rather than half, cadence (singing two "sorrows," the second one going down to G minor, rather than a single "sorrow," going up to D on a D major chord). That RCA Victor would allow such an error to be published is astonishing, going against their usual policy of high standards as it does. The singer and conductor handle it as well as possible under the circumstances (the conductor moves ahead, and after a split second Marsh realizes what has happened and also goes on), but was no one following with a score? Or, was the Great Depression so severe that RCA Victor was unwilling to record another take?

The two bright spots among the principals are Hitzi Koyke (Yum-Yum) and Vera Ross (Katisha). Ms. Koyke is the finest singer in this performance and the only one to give a truly memorable one. Her singing of "The sun whose rays are all ablaze" is beautifully lyrical, if quirky in rhythm (about which more below). At the end, she takes the final phrase up an octave, and floated pianissimo. It is quite a display of talent. Her slight accent does not detract significantly from her performance. Ms. Ross has the heft, vocalism and acting ability to offer a believable and well-drawn Katisha. Her "Oh, living I" is genuinely moving.

The rest of the principals are not especially noteworthy; the best that can be said is that they are adequate. It is probably a safe assumption that this was a company shown to better advantage on the stage, witnessed from the audience, rather than heard only via the cold evidence of an audio-only recording.

One hopes this is true in the case of the chorus, which is, to use a famous epithet uttered by Arthur Sullivan to describe an indifferent orchestra, "often rough." Many times, they are ragged, and inaccurate in rhythm and pitch. The women are better than the men; they are pretty decent in the little snatch they are allowed to sing before "Three little maids" (from "Schoolgirls we, eighteen and under" to the end of the number) and in "Braid the raven hair." But some of the mixed chorus singing, and everything the men do alone, is amateurish.

This was the period just before Fred Waring and Robert Shaw took matters in hand, and really taught America how to sing. Our British counterparts had achieved higher standards many decades earlier, and it certainly shows.

The orchestra is somewhat more proficient than the chorus. The players are, unfortunately, hampered by indifferent conducting and an instrumental arrangement that is only modeled on Sullivan's original (probably by an arranger with a sharp ear). The piano in the orchestra doesn't seem necessary, and sometimes intrudes. The worst added element in this orchestra is a part for snare drum that erupts at singularly inopportune moments, such as in "Three little maids." Suddenly, Sullivan's score sounds like a music track for a cartoon; perhaps this is an outgrowth of the vaudeville tradition.

Throughout the records, there appears to be a determination that the words should not only be heard, but "interpreted" to a degree we are not accustomed to hearing in 1999. It's not even good acting, because so much is fussy without sufficient motivation. That this approach often distorts the music does not reflect well upon the conductor, Louis Kroll. It is impossible to say whether all this emoting was his idea or that of the producer or stage director. Whether or not it was Kroll's, he evidently lacked the force of personality or musical integrity (or both) to impose any significant discipline in the service of the score.

This was a period during which Gilbert's stock was rising while Sullivan's was falling. The company billed itself as "The Only Gilbertian Ensemble In America." If this slogan implied more deference to Gilbert than to Sullivan, the toll upon the musical values is evident in these records.

Aside from the outright errors mentioned previously, Kroll allowed or encouraged an exaggerated tempo rubato that often veered into the crass. Certainly, he led the chorus and orchestra this way.

Some examples:

- In an otherwise impressive "Oh, living I," Katisha speeds up almost comically on the words "When hope is gone, does love stay on" and then immediately shifts gears to a very slow "Why linger here…"

- In the Act I finale, when it comes to Katisha's "My wrongs with vengeance will be crowned," everything just grinds to a halt with a new, very slow tempo, which is carried through the usually stunning final chorus, "We do not heed their dismal sound." Kroll simply kills it; in an attempt to give it weight, which he really is not capable of doing, it just plods in a leaden manner.

- Earlier in the first act finale, the rubato Ko-Ko uses on "…adore myself with passion tenderer still" is distorted, but the following chorus, "Ah, yes he loves himself / With passion tenderer still" is turned into nothing less than a choral recitative (perhaps because Kroll didn't have the skill to take it straight).

It is now almost impossible to find these records. They only were available for about six years, in the United States only, and that during a poor economy. Moreover, because they were only available in Victor's doomed long-play format, very few were made or sold. Listening to them, it is not difficult to understand why. Aside from the detractions of the performance itself, the aural quality is seriously deficient compared with RCA Victor's other product of the period.

This was an era in which the public preferred a booming bass above all else, and indeed these records do quite well in the low end (tympani rolls are well recorded), but the higher range is sometimes so clipped that sibilants are simply inaudible. Add to these deficiencies the considerable surface noise, and the reasons for the swift removal of the long-playing records from the Victor catalogues becomes apparent.

If these records accurately reflect the local standard in the 1930's, one can easily understand why the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company's subsequent visits to New York were greeted with non-modified rapture.

| Date | Label | Format | Number | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb. 26, 1932 | RCA Victor | 10" Double-Sided Long-Playing Records |

L-24005 L-24006 |

Manual side couplings |

| ca. 1933-4 | RCA Victor | 10" Double-Sided Long-Playing Records |

AL-24023 AL-24024 |

Slide automatic side couplings |

Editor's Notes:

- Victor's long-playing records are a footnote in recording history. They never achieved critical mass in the marketplace; it would be American Columbia, in the 1940s, that would introduce (and patent) the LP format that caught the public's fancy.

- Correspondent Russ Karas did not agree with Bruce Miller's assessment of Hitzi Koyke's Yum-Yum. He said, "Her rendition of 'The Moon and I' ('Da Munn an Da'?) is certainly quite memorable, and although she sings this nicely, she squawks her way through the finale in a way that cries out for a retake."

- One oddity is the conductor's name: it is given as Lewis [sic] Kroll on this recording, but "Louis [sic] Kroll" on the companion Pirates set.

- The typical G&S "vocal gems" recording — just one or two 78rpm sides — was extremely popular; there were many dozens of these, possibly hundreds. Such items are generally out of the scope of this discography. This recording is included because, as Bruce Miller describes, it is considerably more substantial than the usual "vocal gems" release.